Section 03: Planning for MEL

Monitoring Evaluation and Learning all need good planning and at the start of any project or programme it is essential that a plan is properly developed. The plan should include:

The rationale and context for the project or programme: a description of the geographic location, the proposed timing, the target group with a rationale why they were selected. (Pest Analysis and stakeholder analysis)

Goals, objectives and indicators: the goal is the wider aspiration of the project or programme; the objectives describe the changes the project or programme intend to bring about; the indicators identify whether progress has been made against the objectives.

Project or Programme design: a description of key working processes, a clear description of what activities will be undertaken over the project period, including an exit strategy.

Key Actors: This will include main partners, and other actors and their role in the project or programme.

Resources: What resources the project or programme need for implementation, including human resources and financial resources.

Risk assessment: What are the risks and how will the organisation manage them or assumptions associated with the project or programme

Monitoring and Evaluation: this should include any baselines completed, how the project or programme will be monitored, when evaluations will be carried out, reporting schedules and details of how learning will be shared both within and outside the project or programme.

Annexes: including a planning tool such as a logical framework, a detailed budget, a detailed M&E plan, an activity or Gannt chart.

3.1: PEST analysis

Why and when to carry out a PEST Analysis

A PEST (Political, Economic, Social and Technical analysis) should be performed at the initial stages of a proposed intervention or if a change is being considered. This will provide the context needed to develop a well planned programme.

In a PEST analysis, you examine four types of factors:

Political factors

Economic factors

Social factors (i.e. forces within society that shape the way people behave)

Technological factors and what is available

PEST: Key strengths and weaknesses

Useful tool to collate information on the wider environment and how those factors will affect your stakeholders.

Can prevent unexpected negative effects of the project coming from the environment that had not been taken into account when entering a new area.

Can be difficult to conduct and may need an external facilitator to assist.

3.2: Stakeholder analysis

First identify your stakeholders – they will be groups of people, individuals, institutions, enterprises or government bodies that may have a relationship with or impact on your project or programme. There are differences in the roles and responsibilities of the different groups and their participation in decision making.

When to complete a stakeholder analysis

Stakeholders’ participation is vital to the successful design and implementation of any project or programme. An analysis of stakeholders should be done at the outset to ensure we fully understand the influence they will have over our work. The analysis will identify and then categorise your stakeholders in a hierarchy of primary, secondary and tertiary stakeholders. By categorising stakeholders in this way it becomes easy to see who and how they should be involved and when.

Primary Stakeholders include those whose interests lie at the heart of the project. These are the ‘beneficiaries’ or the ‘target group’ and are usually users of services your organisation provides.

Secondary Stakeholders are those with whom an organisation co-operates to reach the primary target group e.g. statutory agencies, voluntary groups, private sector organisations and potential co-funders. These stakeholders provide the main support, and they will usually be project/programme partners.

Tertiary Stakeholders may not be closely involved at the beginning but may be important in the long term eg suppliers, customers, contractors, financial institutions, legislative and policy making bodies, external consultants and trading partners. This category may not apply to some projects, but for on-going initiatives can be an important category as they will support the long-term sustainability of the benefits of a project or programme.

An analysis of how they might be involved can be undertaken and you can ask questions to help you consider how and when to involve particular stakeholders and which have the most to contribute and benefit from their involvement.

What are the stakeholders ‘expectations’ of the project/programme?

What benefits are they likely to receive?

What resources will the stakeholder commit or not commit?

What interests does the stakeholder have which may conflict?

How does the stakeholder regard other categories of stakeholders?

What other things do stakeholders think should happen or not happen?

Key Strengths and Weaknesses:

Useful to provide information on the many stakeholders affected by your project.

Can prevent negative effects of the project coming from stakeholders. Easy to do and create a feeling of inclusion for all concerned.

3.3: Theory of Change (often a donor requirement)

A theory of change is a clearly articulated testable hypothesis about how change will occur and the role of a project, programme or organisation in contributing to achieving change. It is an approach to programme design and planning that focuses on what we think will change, not what we plan to do. While the log frame captures a four step logic – input, output, outcome and impact, in reality the pathways through which change happens often have many more steps. These are often interlinked and can move both forward and backward and even skip steps. Theory of change has been developed to help capture that complexity and allows implementers to be accountable for results but also makes the results more credible because they were predicted to occur in a certain way.

3.3.1: Why use a Theory of Change?

Theory of Change needs the whole organisation or programme and their partners or collaborators to commit to a critical and honest approach to answering difficult questions about how their efforts contribute to influencing change.Theory of Change develops a common understanding amongst all stakeholders of what an organisation or programme is trying to change and how. The Theory of Change approach can:

Strengthen clarity, effectiveness and focus of programmes Provide a framework for monitoring, evaluation and learning Help identify strategic partners and conversations around change Can be used to communicate work clearly to others

Supports people to become more active and involved in programmes by explicitly dealing with long-held assumptions.

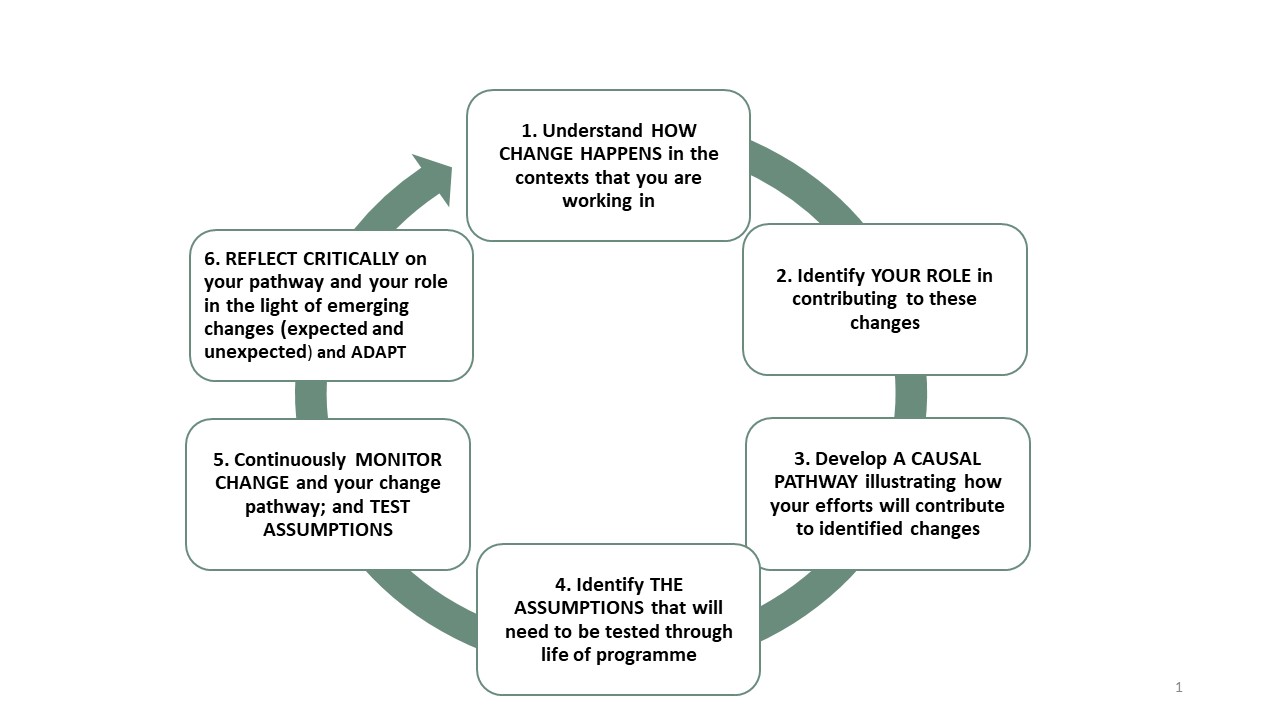

Theory of Change is a cycle of planning and critical reflection involving six stages:

3.4: Logical Framework (often a donor requirement)

The Logical framework is the most common planning tool used by small NGOs. It is the tool of choice for most statutory donors for planning and performance assessment. It was originally conceived as a planning tool aimed at supporting the management of small time-bound projects.

3.4.1: When to use the logical framework

The logical framework is used at the planning stage of any project to assist the project implementers to understand the logic of their intervention. Many donors require a logical framework to be developed before they will consider funding a project.

3.4.2: Why use the logical framework?

There are 3 major advantages to using the logical framework approach:

It ensures that the project planners understand how the activities undertaken in the project relate to helping improve the problem the project is addressing.

It requires the plan to consider how the progress of the project and its success (or failure) will be demonstrated.

By listing assumptions, it takes into account external factors, beyond the projects control which may affect its progress.

3.4.3 Who uses the logical framework?

The logical framework should be completed so all stakeholders are involved in its development. It should be regularly revised through participatory reviews. The logical framework can be used by the management team to monitor the progress of the project. It can also be used by an external evaluator as a description of the planned objectives agreed at the beginning of the project.

3.4.4: How to use the logical framework

The logical framework is based on a simple 4x4 grid that describes what a project or programme needs to do to achieve its goal by outlining a hierarchy of objectives:

The Goal/Aim: The highest-level objective which an intervention is designed to contribute towards achieving.

The Outcomes: The planned or achieved short-term and medium-term changes that occur as a result or consequence of an intervention’s outputs.

The Outputs: The tangible products, goods and services (and other immediate results) produced as a result of the activities carried out by an intervention.

The Activities: The collection of tasks to be carried out in order to achieve an output.

The Inputs: The financial, human and material resources needed to carry out activities.

3.5: Setting objectives / goals

What is an Objective/Goal

An objective describes a change a project, programme or organisation wants to achieve by a planned development intervention. Objectives can be at multiple levels from broad strategic organisational objectives to very specific project objectives.

Setting good clear objectives makes monitoring and evaluation much easier and more effective. Below are the three main levels of objectives:

Goal/Aim or Impact is the highest-level objective which an intervention is designed to contribute to (these can be positive and/ or negative, lasting changes produced by a development intervention) and could be produced directly or indirectly by the project and be intended or unintended changes (i.e. Did the intervention make a difference? To whom? Were there unintended effects?)

Outcomes are the planned or achieved short-term and medium-term changes that occur as a result or consequence of an intervention’s outputs.

Outputs are the tangible products, goods and services (and other immediate results) produced as a result of the activities carried out by an intervention.

Developing objectives at outcome level are the ones that cause most problems. An important reminder is that outcomes need to be linked to the problem you want to address and what you need to do to achieve change (not what you are going to do).

What is the problem?

What do we want to change?

Output or outcome?

Here are a few examples of the difference between outputs and outcomes.

Developing Objectives

In any project or programme there is likely to be a hierarchy of potential objectives at different levels ranging from outputs or short-term, small-scale changes through to Impact or longer term wider changes. This can cause problems for project or programme planners when setting objectives at the start of a development intervention.

An example taken from the M&E Universe paper on setting objectives illustrates this using a set of objectives derived from an HIV&AIDS awareness-raising project. In this project, training sessions on HIV were given to university lecturers in order to enable them to provide better information to their students. In turn, this was expected to result in better understanding amongst students, and eventually changed behaviour, leading to lower transmission rates.

3.6: Developing Indicators

What is an indicator ?

A quantitative or qualitative variable, related to the objectives of a development intervention, that provides reliable ways of assessing (indicating) whether progress has been made or change has taken place.

Indicators are an important element of any monitoring and evaluation system.

We can define an indicator as an observable change or event which tells us that something has happened. It is not proof but a reliable sign that the event or process is actually happening or has happened.

There are two types of indicators:

Quantitative indicators are reported as numbers, such as units, prices, proportions, rates of change and ratios.

Qualitative indicators are reported as words, in statements, paragraphs, case studies and reports.

Note that it is not the way in which an indicator is worded that makes it quantitative or qualitative, but the way in which it is reported. If an indicator is reported using a number then it is a quantitative indicator. If it is reported using words then it is qualitative

In addition to quantitative and qualitative indicators, there are also other kinds of indicators.

If you want to understand more on the different types of indicators please refer to the M&E universe paper on indicators.

Until recently, many indicators were developed according to the Quantity, Quality, Time and Place (QQTP) protocol. This meant that an indicator would be defined to be specific about these four elements, as in the example below:

Although many organisations still define indicators in this way, a new industry standard is emerging, where indicators increasingly appear as neutral statements (e.g. ‘# of new jobs created’, not ‘50 new jobs created’). These indicators do not contain specific numbers, and should not include words such as ‘increase’, ‘reduction’ etc. The intention is to ensure that indicators remain as neutral criteria providing evidence of change, rather than targets to be achieved.

Whether neutral or not, a good indicator is still expected to be specific about time and place. It should be clear which target groups are covered by the indicator and what are the expected timescales for change. In the example above the quantity would be # of midwives.

3.7: Developing an MEL Plan

It is important to develop a formal written MEL plan at the beginning of any programme or project that identifies how the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning will be done. The plan should be linked closely to the strategic plan or project/programme plans. It is important to agree how MEL will be conducted at the planning stage for example how will you set objectives, what indicators will you be measuring, will a baseline be completed and what tools will you use collect the data.

It is also important to agree how plans will be developed as this will affect who gets involved in the monitoring, evaluation and learning processes. For example if you want a participatory MEL system then you will need to involve the communities in planning your MEL and how they will use it. They will need to identify the problems, helping with suggesting solutions and included in developing objectives and indicators. It will also be important to get communities involved in agreeing how the data will be collected particularly if you want them to do the collection and be involved in the analysis of the data collected.

You can download a MEL plan outline here.

Last updated